Daft Punk, Nostalgia, and Musical Conservatism

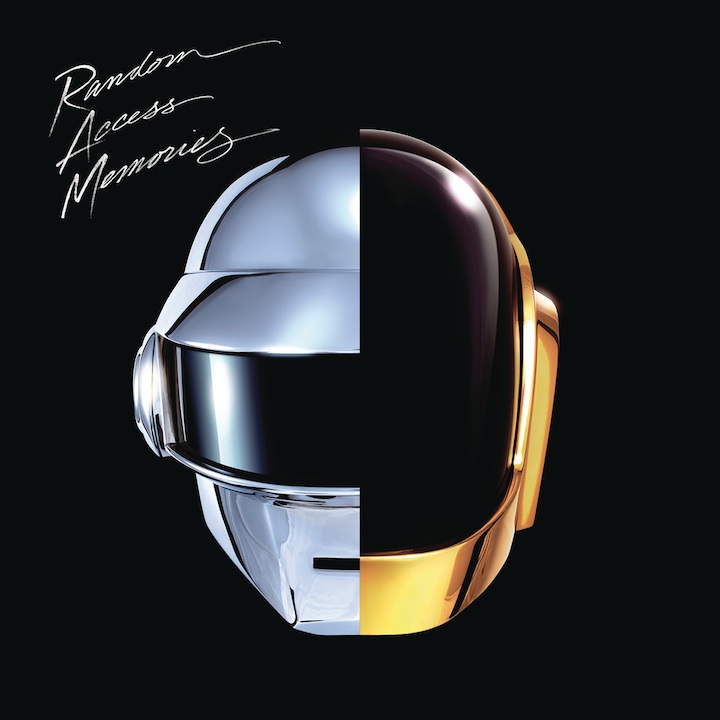

There’s no reason not to be very happy for Daft Punk right now. The French production duo, who have been making music since 1993, recently won five awards at the 56th Annual Grammy Awards—including both Album of the Year (for Random Access Memories) and Record of the Year (for ‘Get Lucky’). They also demonstrated exactly why they deserved the accolades by putting on a phenomenal live performance with Pharrell Williams, Nile Rodgers, and Stevie Wonder: a medley of ‘Get Lucky’, Chic’s ‘Le Freak’, and Wonder’s ‘Another Star’. Over two decades of hard work and perseverance by a group twice removed from the mainstream (by both nationality and musical genre) finally rewarded on the music industry’s night of nights—how could you not feel good about that?

Despite this heartwarming conclusion to Daft Punk’s underdog narrative and my own 14-year love affair with the robot-helmeted duo’s work, I found myself strangely unmoved by this long overdue recognition. Even though a dance music album hadn’t won Album of the Year since the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack in 1979, electing Daft Punk as the recipients of the major gongs at this year’s Grammys doesn’t feel at all visionary of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. It instead confirms what most music aficionados already know about the Grammy Awards: that the Academy has largely played it safe for well over a decade. Since Daft Punk don’t fit the profile of the average Grammy winner, the reason this decision feels so conservative comes down to Random Access Memories.

Random Access Memories might not be a conservative record itself—it takes some incredible artistic risks, such as including an eight-minute pop opera—but it certainly is a deeply nostalgic one. Recorded to magnetic tape on vintage AMPEX machines at some of the most iconic studios in American music history—Electric Lady, the studios in Hollywood’s Capital Records building, and the former A&M studios—with session musicians who had appeared on albums by Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Lionel Richie, Madonna, and Herbie Hancock, the album’s very mode of production speaks of a nostalgia for twentieth century recording practices made viable by the industry’s then-ripe profits. (One unavoidable way Daft Punk have kept up with the times is by footing the bill for recording Random Access Memories, estimated to be over a million dollars, rather than relying on the largesse of their label, Columbia.)

Fittingly, most of Random Access Memories’ songs are pastiches—a blend of classic disco’s crisco-slick melodies, prog rock theatrics, west coast Americana, and the muted yet unctuous grooves of ‘quiet storm’ R&B. It sounds, in short, like an album that could have been produced at any stage between 1977 and the present, with only a few touches of electronic frippery. And while its commitment to rich, organic sounds is completely out of step with the dayglo synth sounds of EDM—the popular dance subgenre du jour—it’s very much in tune with the musical priorities of the present: cut from much the same cloth as the retro syncretism of Haim’s Days Are Gone, and reaping the same rewards of mainstream success.

There has always been an element of temporal displacement about Daft Punk’s music: Homework, their 1997 debut, scuffed up the slickness of 90s house with the energy of punk rock; 2001’s Discovery made crate-digging cool for over a decade through its judicious use of rare disco samples; 2005’s Human After All prefigured dance music’s noise turn even as it emerged to critical bafflement. Since that’s the case, I’m sure Daft Punk will forgive my own hopeless nostalgia for a time when they used their temporal displacement to challenge the status quo, rather than pandering to our contemporary desire for safe music from an idealised past.