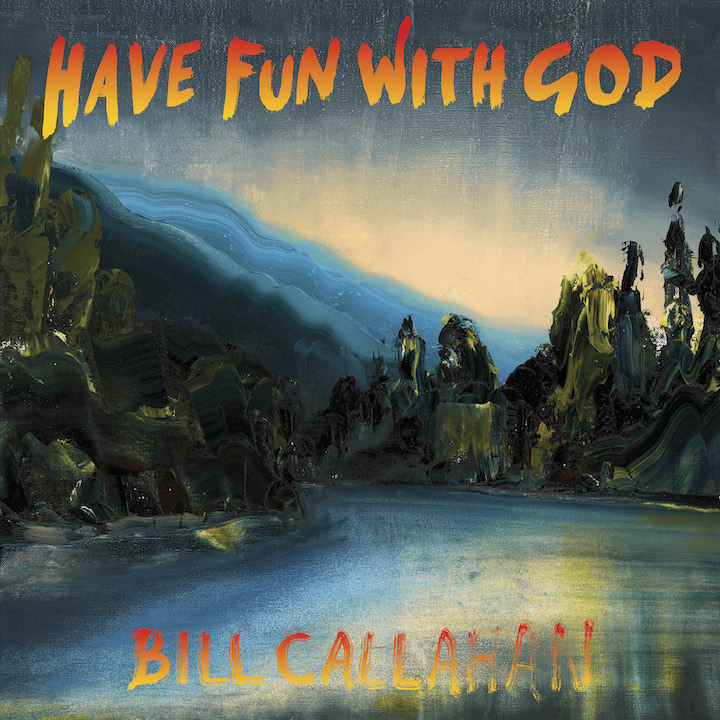

Bill Callahan’s Have Fun With God

If the world needed any further proof that Bill Callahan has an almost pathological contrarian streak, he delivered it last year when he promoted his then-forthcoming album, Dream River, by releasing a dub version of one of its highlights, ‘Javelin Unlanding’. Aside from the perversity of promoting an album by way of music that would not appear on it, Callahan’s choice to release ‘Expanding Dub’ as Dream River’s lead single revealed the artist’s heretofore unknown love for dub music. As he explained in an interview with the Quietus last year, “Dub is a spiritual, abstract, visceral, mystical thing. Finite and infinite at the same time. Deeply rooted in the earth and in outer space. It was invented in Jamaica and no one else really messes with it as it is greatly abetted when the original song has a reggae rhythm, which my songs largely do not.” Despite the caveat that his songs are seemingly not suited to dub treatment, Callahan has produced not only a dub version of ‘Javelin Unlanding’ but also dub versions of each of the other seven songs that appear on Dream River, all of which have been collected on Have Fun With God.

Appropriately enough, Have Fun With God sticks to the same track order as Dream River, which makes it analogous to Burning Spear’s landmark dub album Garvey’s Ghost (itself the dub doppelgänger of Burning Spear’s previous album, Marcus Garvey). The title Garvey’s Ghost gives an insight into the contested etymology of the word ‘dub’: it could be a shortening of the English ‘double’, as in a duplication of an original, or it could come from the Jamaican Patois word ‘duppy’, for ‘malevolent spirit or ghost’. These meanings are, of course, not mutually exclusive, and part of dub’s appeal is the way it both duplicates its original and simultaneously transforms it into something ethereal—flesh made spirit. (Little wonder, then, that dub music is used both for the worldly pursuit of pleasure through dancing and also as a means of expressing Rastafari spirituality.)

Dub as a genre therefore points towards both death and the afterlife, just as sleep and dreams have for a long time represented both the ‘big sleep’ to come and the possibility of life beyond this life. And while the surface of Callahan’s Dream River remains mostly unperturbed by the subject of mortality, death lurks as an undercurrent in many of the songs: a necessary corollary of fertility in ‘Spring’, conjoined with coitus in ‘Ride My Arrow’, an ever-present danger in the journeys that comprise ‘Small Plane’ and ‘Winter Road’. In this sense, Dream River provides thematically suitable fodder for dub versions—even if, as Callahan admits, his music is rhythmically and melodically quite far removed from reggae.

Indeed, listeners expecting dub music in its traditional sense will be deeply disappointed by Have Fun With God: there are no echoing horn licks, no staccato guitar chords on the offbeat, no rolling drum fills to introduce each new song. (I imagine Have Fun With God’s utility for sparking up is relatively limited.) Callahan’s interest in dub isn’t so much rhythmic or formal as technical and structural—he’s interested in the possibilities opened up by extending and emphasising these songs’ rhythm tracks, stripping the other parts back to a bare minimum, and drenching what remains in reverb. Callahan’s lyrics, usually the centrepiece of his music and for which he has been rightly lauded, drop in and out as he pleases. How well this works in any given case depends on the song itself—while there’s plenty to strip back from the pleasantly overstuffed ‘Javelin Unlanding’, Dream River opener ‘The Sing’ is already a masterpiece of elegant understatement, which makes its dub version, ‘Thank Dub’, somewhat soporific. The Dream River songs with big, dramatic crescendoes—particularly ‘Spring’ and ‘Summer Painter’—fare better, with their squalls of guitar noise and splash cymbals providing rich textural detail even when smeared to a paste by reverb. The hurricane in the narrative of ‘Summer Painter’ sounds absolutely cataclysmic in ‘Summer Dub’; by contrast, the ‘dream river’ section of ‘Seagull’ sounds even more dreamy and languid in ‘Transforming Dub’. As a whole, though, the dub versions collected on Have Fun With God are rather etiolated compared to their more musically robust siblings from Dream River, and it’s certainly fair enough to say that Have Fun With God at the very least requires its listener to be well-versed in Dream River before its own charms can be made manifest.

Have Fun With God therefore doesn’t make much sense as a standalone album, and some might wonder why Callahan – whose past music has often achieved its profundity by saying as little as possible both melodically and lyrically—would bother releasing an album that’s clearly a fans-only curio. But even if Have Fun With God occasionally meanders or strips its source material back a little too far, its value lies in the way it extends the course of Dream River (which itself sounds like a continuation of Callahan’s 2011 magnum opus, Apocalypse). Listening to these ghostly versions of Dream River’s tracks, I imagined a dizzying, Borgesian series of albums, each stripping back and elongating the music of its predecessors until only the purest, most subtle drone tones remained. If Dream River has all of the ease and contentment of a summer day spent swimming in a freshwater creek in some pastoral idyll, then Have Fun With God captures the moment when the sun begins to sink and the water becomes uncomfortably chilly: we know we need to leave, but we remain as long as possible, vainly attempting to hold on to our pleasure, vainly attempting to delay the inevitable.