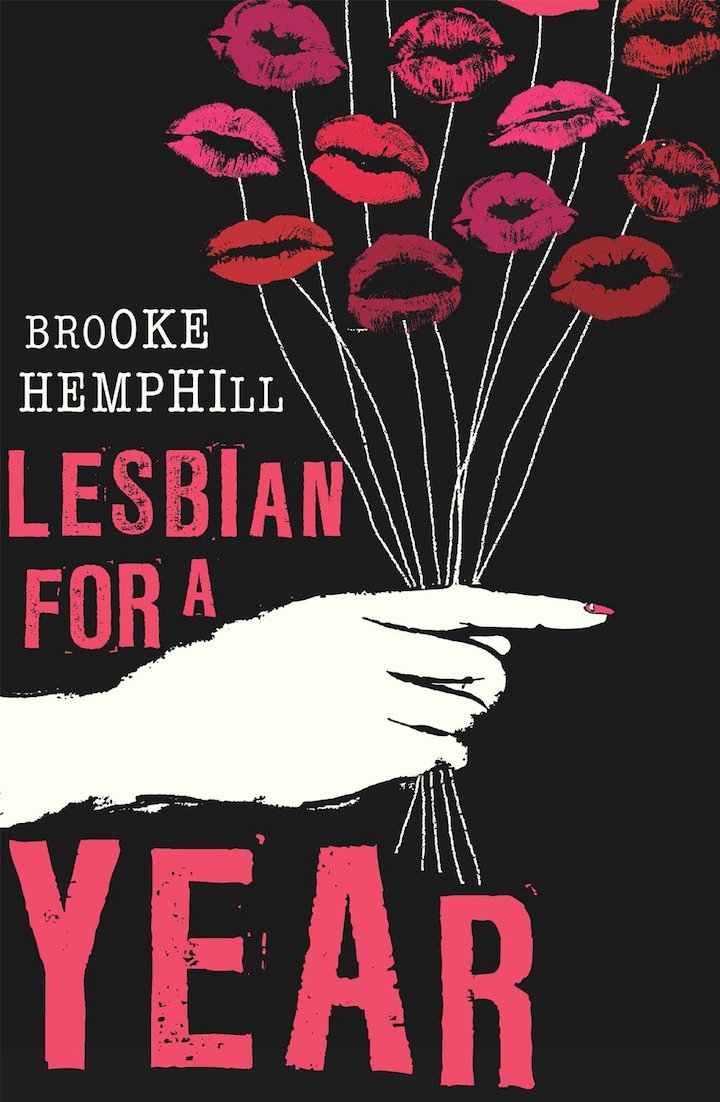

Brooke Hemphill’s Lesbian for a Year

Brooke Hemphill’s debut book, a memoir titled Lesbian for a Year, raises some very interesting questions—just not the ones that Hemphill herself would like to raise. Rather than focusing on issues of sexual fluidity and the arbitrariness of sexual identity, much of the discussion about Lesbian for a Year has centred around the offensiveness of the title and the memoir’s general conceit, as well as raising questions about how the book ever managed to get published in its current form.

The backlash against Hemphill from within the queer community has been relatively swift and ferocious. Carody Culver tore the book’s premise to shreds in a Junkee article; Shirleene Robinson expressed dismay at the book’s shallow understanding of lesbianism in The Conversation; and members of Australia’s lesbian community weighed in on the comments section of Mamamia’s interview with Hemphill.

For her own part, Hemphill has used the controversy as an opportunity to play victim—she claimed in her Mamamia interview that she experienced less discrimination and prejudice during her lesbian year than she since has from the LGBTI community since the release of the book, she’s given interviews about being “shocked” by the backlash, and has flounced off Twitter due to others “being unnecessarily nasty”.

Her publishers, Affirm, and her agent, Virginia Lloyd, are currently in damage control mode: Affirm has taken to pasting pro-forma responses in comments sections about the book, claiming that all discussion about sexual identity is good discussion, and Lloyd has been rather frank about the salaciousness of the title in an attempt to portray the book as more nuanced than its title might suggest.

The criticism of the book has, by and large, been thoughtful—and any anger expressed at its insensitive title might be more accurately thought of as an expression of the seriousness with which lesbians identify as lesbians than simply the bitter rantings of some pack of “Twitter trolls” who “haven’t done their due diligence”. (Much of the defence of Hemphill’s book includes the helpful suggestion that anyone who wants to criticise it should go out, purchase a copy, and read it before doing so.) However, the discussion has thus far elided some of the thornier issues that the book itself, in its own inarticulate way, raises.

Compulsory Heterosexuality

Readers looking for the tales of sapphic lust that the book’s title promises will be sorely disappointed by Lesbian for a Year: Hemphill’s year of lesbianism takes up, by my count, only 75 of the book’s 233 pages, and the few lesbian sex scenes are described in a clinical and detached tone. The vast majority of the book actually discusses Hemphill’s straight life, and the long parade of dickheads that she dated prior to her year of switching teams.

Hemphill’s previous beaux form a sorry group portrait: there’s Corey, the boy to whom she loses her virginity in lieu of the more attractive Shane; there’s Andrew, her first serious boyfriend, who pressures her into an engagement at the age of twenty in an attempt to stop her from travelling to the United States; there’s Leonardo, her skeevy middle-aged boss with whom she cheats in order to back out of her engagement to Andrew; there’s Jake, a cad who holds out the promise of intimacy in exchange for a few drunken quickies; there’s Chad, whose idea of making love is, in Hemphill’s words, “almost as if he’s doing push-ups on top of me”; and there’s Darren, who gets Hemphill pregnant either by not knowing how to put on a condom properly or by deliberately removing it while she has temporarily blacked out from drug use.

Reading through this litany of banal heterosexual horrors, I couldn’t help but be reminded of Adrienne Rich’s essay ‘Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence’, which argues that heterosexuality is not so much a sexual identity as a cultural construct that enforces male privilege upon women’s bodies and affective labor. Rich, following Kathleen Gough, identifies no fewer than eight characteristics or mechanisms of male power that produce heterosexuality in women—some of which do not necessarily apply to Hemphill’s own life as it is described in Lesbian for a Year, but others of which absolutely do.

For example, Hemphill loses her virginity to Corey not because she wants to have sex with him but because of the cultural expectation that she ought to lose her virginity before graduating high school (characteristic two: to force male sexuality on women). Andrew proposes to her in order to ‘keep’ her from travelling to the United States and realising her creative ambitions (characteristic five: to confine women physically and prevent their movement, as well as characteristic seven: to cramp their creativeness), and she agrees to marriage because of the inordinate pressure brought to bear by both her own family and Andrew’s (characteristic six: to use women as objects in male transactions). Later, when Darren gets Hemphill pregnant through his accidental or deliberate misuse of the condom, he escapes the burden of having to deal with the issue (characteristic three: to command or exploit women’s labour to control their produce).

Hemphill is clearly sexually attracted to men, and she is interpellated as heterosexual by her family and broader community. Despite this, while reading overLesbian for a Year I was struck by just how poorly her own sexuality fits with broader social models of heterosexuality: she finds most of her male lovers subpar in the sack (and talks freely of needing to ‘take matters into her own hands’ in order to orgasm), and none of them seems to provide her with the kind of emotional fulfilment that she seeks from them, with the exception of Antonio, the man with whom she has shacked up at the conclusion of the book. Far from being a memoir about her time batting for the other team, Lesbian for a Year could more properly be described as a memoir about the sheer awfulness of a certain socially-sanctioned form of heterosexuality: one in which women are covertly and overtly pressured into allowing men access to their bodies, in which men don’t care for erotic reciprocity, and in which men are encouraged to toy with women’s emotions in order to make them craven, exploitable beings.

What Makes a Lesbian a Lesbian?

Much of the heat that Lesbian for a Year has received has centred around its deployment of the word ‘lesbian’ in the title. This, in turn, revolves around a fear that a book such as Lesbian for a Year might imply that homosexuality is a ‘choice’—and the notion that homosexuality is a ‘choice’ pops up with alarming frequency in fundamentalist Christian discourse. Culver, for example, asks: “Why, in 2014, are people like Hemphill continuing to perpetuate the myth that you can choose your sexuality?”

Certainly, Hemphill’s own approach to her year as a ‘lesbian’ is remarkably cavalier. She begins it by drunkenly taking home a woman and having unsafe sex with her (no dental dams, no condom on the sex toy Hemphill uses to pleasure her partner). Only the morning after this episode does she start to interrogate the experience, and uses it as something of a launching pad for her year of dating only women. During this year—which at first seems completely unplanned and later begins to resemble the year of structured abstinence Jill Stark took for her successful memoir High Sobriety—Hemphill seems keen to perform a certain version of lesbianism. She doesn’t hang out with a diverse cross-section of the LGBT community, but rather with a small handful of the “gay-list”: wealthy, presumably white and upper-class, successful lesbians from Sydney’s eastern suburbs. When she wants to read up on the lifestyle, she checks out not books about lesbian history or the construction of sexual identity but things like The History of Lesbian Hair and The Sex Lives of Famous Lesbians.

Perhaps most damning, Hemphill throws the word ‘lesbian’ around as though it’s going out of fashion: it’s not afternoon tea, it’s lesbian afternoon tea; it’s not TV, it’s lesbian TV; it’s not a night out, it’s a lesbian night out. As she writes, “It’s as if maybe if I say it enough times, it won’t feel so foreign.” Hemphill seems, in short, to be interested in performing a certain kind of lesbianism rather than wholeheartedly committing to that identity. (I don’t mean performing here in the Judith Butler/Gender Trouble sense of the term, where the performance comes to constitute the identity; I mean it in the simpler sense of play-acting, make-believe.)

Unlike Culver, I don’t want to be too hasty in condemning the idea that sexuality, and particularly lesbianism, is a ‘choice’. I have met women who did in fact make a conscious decision to become lesbians after reading lesbian separatist feminist texts; they very simply decided that sleeping with men would be propping up the patriarchy, and ceased doing it. Some soon found that they were actually rather suited to their chosen sexual identity. Similarly, I have met women who identify as lesbians but occasionally sleep with men. For these women, what makes them a lesbian is not to do with the genitals of who they sleep with but to do with the gender of the people with whom they form lasting relationships and become part of a broader community. There are many different ways to be a lesbian, just as there are many different ways to be gay, straight, bi, or asexual. What is clear, however, is that Hemphill’s engagement with both the lesbian community and the broader queer community is, at least on the evidence of Lesbian for a Year, not sufficient to merit the label.

In a way, the publication of Lesbian for a Year might be seen as the apotheosis of a certain assimilationist conception of queer sexuality: the idea that there’s nothing special or different about gays, lesbians, bisexuals and other queers except the genitals of the people they sleep with. This conception of sexuality is the main driver behind the push for gay marriage, the politics of acceptability, and projects such as Just Like You, which attempts to show straight audiences that queer couples aren’t all kinky deviants who get around the house in leather and vinyl and have poppers and MDMA for dinner. We might therefore be tempted to see the publication ofLesbian for a Year as a triumph for the LGBT community: we’re now so banal that a heterosexual woman can pick up a lesbian identity for a year or so, write a book about it, and complain that the toughest time she had of it was after the book was published. This is certainly an improvement upon the social and legal censure that would have followed this book’s publication in, say, 1980.

Perhaps more heartening, however, is that a book with such an inflammatory title and such a shallow view of sexual identity has caused such a strong backlash from the broader LGBT community. The anger that this book has provoked shows that the politics of respectability and assimilation haven’t completely triumphed over antiassimilationist and communitarian understandings of queerness. This anger shows that there’s a lot more to being queer than just the kind of genitals your sexual partner/s possess—it’s also about being part of a community, sharing a history, and partaking in a certain queer orientation towards life itself.