X-TG’s Desertshore

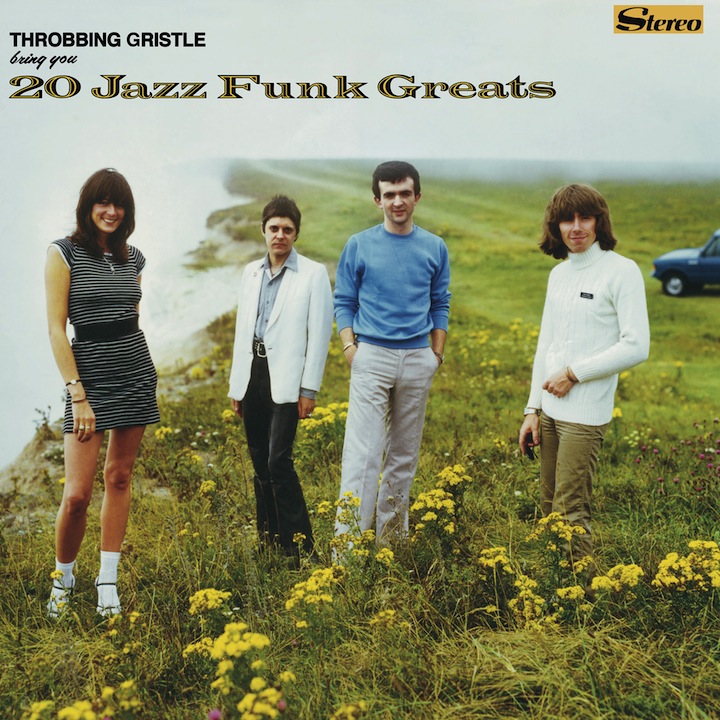

It’s easy, and inaccurate, to reduce Throbbing Gristle to a band obsessed equally with sex and death; but that doesn’t mean that they weren’t obsessed with those very topics. Take the cover of their seminal 1979 album 20 Jazz Funk Greats: a lovely shot of the four members of the band on the heath at Beachy Head, Britain’s foremost suicide location. As for sex, that album includes the proto-techno track ‘Hot on the Heels of Love’, where Cosey Fanni Tutti pushes the human/machine coupling of Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ and pushes them further into the cybernetic field—where Summer’s vocalisations sound like a performance of sex, Tutti’s insouciant moans sound, more shockingly, like sex itself. But their true obsession was the infinite, the inconceivable beyond to which both sex and death continually point.

For a band that was so preoccupied with endings and what lay beyond them, their own end was ignominiously swift. After breaking up in 1981, all four original members of the band—Chris Carter, Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson, Genesis P-Orridge, and Cosey Fanni Tutti—reformed in 2004. They recorded two new albums in the following years and were at work on a third, a front-to-back cover of Nico’s celebrated 1970 album Desertshore. Then, in October 2010, P-Orridge refused to perform in the final dates of the band’s world tour. Carter, Christopherson and Tutti completed the tour under the name X-TG, and shortly thereafter—less than a month after P-Orridge broke with the group—Christopherson died in his sleep. Whatever plans the four members may have had to reconcile their differences, Throbbing Gristle was no more.

In the absence of Christopherson, and with P-Orridge remaining uncooperative, Carter and Tutti have set themselves up as the custodians of Throbbing Gristle’s legacy, remastering and reissuing five of the band’s albums last year. Desertshore (released with a companion disc entitled The Final Report) continues this work, albeit in a more involved way: the Desertshore recordings were nowhere near completed, after the band decided to scrap their first attempt at it. After Christopherson’s death, Carter and Tutti approached several vocalists that Christopherson had admired to help them complete the record. Armed with the original recordings, new recordings by Christopherson, and these guest vocal tracks, they set about synthesising a definitive release. This final version of Desertshore is therefore a unique document: it is a posthumous testament to the power and fruitfulness of a creative bond between three remarkable individuals.

The source material is, of course, an integral part of what makes X-TG’s Desertshore so affecting. Nico’s own Desertshore is a famously difficult album—full of long harmonium drones, plinking harpsichord, and raggedy strings courtesy of John Cale’s unorthodox arrangements—and one that feels glacially-paced, even though its eight tracks speed past in under half an hour. There’s a sparseness to the album quite in keeping with its title, which allows for moments of utter heartbreak and beauty. Indeed, it’s fair to say that X-TG’s Desertshore doesn’t quite have the impact of Nico’s original—but this is hardly a withering criticism, since both records have completely different aims.

The opener of X-TG’s Desertshore, ‘Janitor of Lunacy’, makes the differences between the two projects plain. Where the original is carried along in a gyre of harmonium tones, this version resonates with a low pulse augmented by chittering digital blips in the high end—one of Christopherson’s favourite tricks. Over the top of this chillingly perfect soundscape comes a career highlight of a vocal take, courtesy of Antony of Antony and the Johnsons. X-TG’s ‘Abschied’ sounds to my ears like a polished update of Horse Rotorvator-era Coil—the tinny military snare drums and clink of finger cymbals (or are they coins?) bring to mind both ‘Ostia (the Death of Pasolini)’ and its coda, ‘Herald’. Einstürzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld adds an appropriate amount of Sturm und Drang to Nico’s German-language lyrics. As far as radical deconstructions go, ‘Le Petit Chevalier’ is unrecognisable—sung by film director Gaspar Noé, it’s as much of an auditory overload as his film Enter the Void is a visual one, Noé’s voice garbled beyond all recognisable humanity and intoning the threatening promise of the petit chevalier, “j’irai te visiter” [“I will visit you”]. Where Nico’s version of the song achieves its menacing effect by matching the lyrics with the singsong voice of her young child, X-TG’s version renders the voice of the song as pure, terrifying alterity.

My two favourite tracks from X-TG’s Desertshore are ‘The Falconer’ and ‘My Only Child’, and given the tenderness of the vocal takes, it comes as no surprise to find out they were delivered by two of Christopherson’s closest friends and collaborators. ‘The Falconer’ is delivered by Soft Cell’s Marc Almond, who has recorded with Christopherson’s post-Throbbing Gristle project Coil. The ubiquity of Soft Cell’s cover of ‘Tainted Love’ has rendered Almond’s voice unsurprising, but this track—where Almond double-tracks his voice an octave apart—restores its strangeness and beauty. The vocals on ‘My Only Child’ come courtesy of X-TG’s own Cosey Fanni Tutti, and speak of her own deep emotional connection to the late Christopherson. It’s hard not to listen to this song — originally written by Nico as a hymn to her only child, Ari Boulogne—without thinking of Tutti as a mother sending her child alone into the great beyond, full of sorrow that she cannot guide him. In many ways ‘My Only Child’ is the emotional crux of X-TG’s Desertshore—it appears early on Nico’s Desertshore, but X-TG’s is rearranged so ‘My Only Child’ is the penultimate track. Which leads us to the final track, and the sole original composition on the album, ‘Desertshores’. Against a spare backdrop of a simple piano figure and monastic chants, a succession of Christopherson’s friends and collaborators utter a single line: “meet me on the desertshore”. It’s a profound elegy for a man whose musical career plumbed the depths of sonic ugliness and tore at the very seams of music, always looking for ways to move ahead, leave behind the formulaic, and go beyond.