Oliver Sacks’s Hallucinations

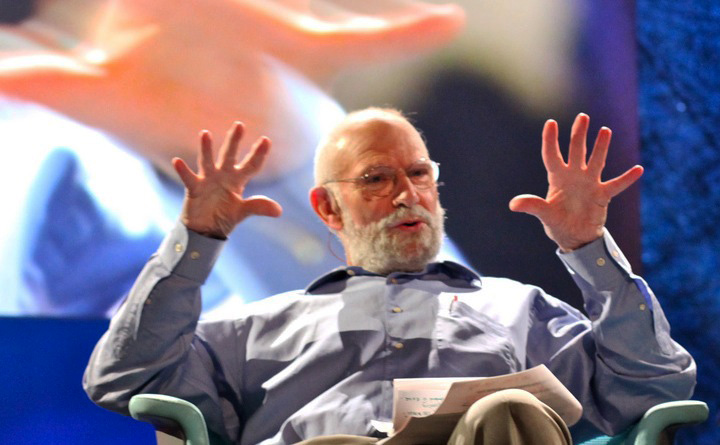

It’s not hard to see why US-based British doctor and writer Oliver Sacks has become, for many people, the chief ambassador for neurology. His books render this forbiddingly dry subject accessible by cutting to the core of what neurology means for a lay audience.

Rather than focusing on structures such as the hippocampus or the effects of chemicals such as dopamine, he instead illustrates their functions through case studies of patients with neurological disorders.

This humane touch has its roots in a wide-ranging humanism evident in Sacks’s best-known book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985), in which he neatly and unpretentiously discusses Nietzsche, Borges and Pope’s Dunciad alongside his patients’ pathologies.

He has also, through time, become an excellent writer, attuned to the primal appeal of narrative in nonfiction. As his parallel career as a writer has progressed, his books have become ever more populated with case studies presented as narratives or anecdotes.

His new book, Hallucinations, operates in a mode familiar to readers of his recent work. Sacks presents us with various forms of hallucinations and sketches case histories of several people who experience these.

Many of the case studies are fascinating: consider the woman who experiences strong unpleasant smell hallucinations and soon has to radically alter her diet just to bring herself to eat food at all. Other patients report seeing entire tableaus of hallucinatory figures and taking great pleasure in their coming and going, or tactile hallucinations that cover all surfaces in a pleasant but faintly disturbing film of peach-like fuzz.

Through these examples Sacks takes us on a Cook’s tour of hallucinations, explaining not only their causes (head trauma, the ingestion of mind-altering drugs and so on) but also the role of the neurological structures involved in each case.

Sacks’s life is often his greatest case study, and he has experienced a large number of hallucinations that he describes with the elegance and charm on display in his 2001 memoir Uncle Tungsten. His chapter on aural hallucinations returns to the scene of the opening chapter of his 1984 book A Leg to Stand On, detailing how an external voice cut through his internal dialogue at a moment of great physical danger. Similarly, the chapter on hallucinations caused by migraines opens with his first experience of a migraine aura at a very young age.

Perhaps most interestingly, the chapter on drug hallucinations deals frankly with Sacks’s extensive experiments in mind-altering drugs. These misadventures are initially amusing: after two puffs of a joint containing nothing but marijuana, Sacks sees his own hand “stretched across the universe, light-years or parsecs in length … this cosmic hand somehow also seemed like the hand of God”.

But as his explorations deepen, we witness an obsessive nature that sees him taking ever-larger and more dangerous doses of recreational drugs, until he has a hallucinatory meltdown on a New York City street. (He is rescued by a colleague, Carol, who says: “Oliver, you chump! You always overdo things.”)

While there is much to enjoy in Hallucinations, it also reveals the limitations of Sacks’s urbane, narrative-driven intellectual method. Because his books focus on a kaleidoscope of individual case studies, they don’t form theories or arguments. Hallucinations presents no grand unified theory of hallucinations and their significance for our understanding of what it is to be human. Where a thinker like Freud (or, better, Maurice Merleau-Ponty) would have used these case studies as the basis for outlining a deeper theory of personality, Sacks avoids drawing such conclusions from them.

Indeed his method explicitly repudiates Freud’s: where dreams functioned as the “royal road” to the unconscious for Freud, Sacks warns us not to take hallucinations as manifestations of some hidden aspect of our personalities or cognition. “A religious person might hallucinate praying hands or a musician might hallucinate musical notation, but these images scarcely yielded insight into the unconscious wishes, needs, or conflicts of the person,” he writes.

Moreover, Sacks actively tries to forestall readers from drawing certain conclusions from his work. A chapter on the hallucinations of divinity and the sacred that often accompany epilepsy leads him to wonder if there might be a neurological basis for our species’ near-universal feelings of spirituality. If this were proven to be the case, it would be a devastating blow for organised religion and a triumph of the secular rationalist viewpoint represented by Richard Dawkins and his “new atheist” colleagues. Perhaps trying to forestall controversy, Sacks adds a caveat: if religiosity has a neurological basis, “it says nothing of the value, the meaning, the ‘function’ of such emotions, or of the narratives and beliefs we may construct on their basis”.

Hallucinations is deftly written, entertaining and informative, but despite Sacks’s well-known humanism, it perversely shies away from tackling the big questions, even when the author’s research leads him right to them.