Talking Heads’ Speaking in Tongues Revisited

When Annie Clark, better known as St. Vincent, took to the stage for an encore with David Byrne at Hobart’s MONA FOMA festival on January 20 of this year, she began by recounting her first encounter with Byrne’s music. At a tender young age she had watched Jeff Kanew’s 1984 film Revenge of the Nerds—a film released when Clark herself was only one year old—and heard the Talking Heads song ‘Burning Down the House’, cleverly synced with a scene where jock fraternity the Alpha Betas accidentally burn down their own lodgings. Byrne’s music—and Talking Heads’—was, she continued, already part of the fabric of American popular culture by that stage, and her now thirty-year-old self can still barely believe she has the honour of recording and touring with him.

Although this anecdote is, no doubt, a well-rehearsed piece of stage banter, the warmth and humility with which Clark told it demonstrated that her wonderment at sharing a studio and stage with Byrne was not an affectation. Talking Heads’ and Byrne’s music has indeed become part of the fabric of twentieth century popular culture—not just in America, but throughout the globe. And, like Clark, many of us were first introduced to Talking Heads’ music through ‘Burning Down the House’, the lead single from their 1983 album Speaking in Tongues. Despite the reverence with which the Heads are now held by the institutions of American popular culture, it’s worth noting that ‘Burning Down the House’ remains their only top-ten single on the US Billboard Hot 100, peaking at number nine; it attained similar chart positions in Canada and New Zealand. Paradoxically, it didn’t make the charts at all in the UK, despite the fact that the UK market was historically much more sympathetic to Talking Heads’ music (‘Once in a Lifetime’ and its album Remain in Light had been modest successes there). Australians, too, shared this indifference for ‘Burning Down the House’—it peaked at number ninety-four.

The mixed reception of ‘Burning Down the House’ is symptomatic of Speaking in Tongues’ current standing in Talking Heads’ oeuvre. Shortly after its release it became their most commercially successful album, and arguably did much of the heavy lifting required for their next studio effort, Little Creatures, to become the best selling of all their albums. At the same time, it is frequently critically overlooked, with most retrospective accolades falling to its predecessor, 1980’s Remain in Light. (In this quantitative moment of clickbait list-articles it would be remiss of me not to mention that, of all of Talking Heads’ albums, Remain in Light has performed the best in critical round-ups since, being the highest-ranked Talking Heads album in Rolling Stone’s ‘500 Greatest Albums of All Time’ and both Slant and Pitchfork’s lists of 1980s albums.) How are we to understand Talking Heads’ fifth studio album, thirty years on—as a stepping stone in their incremental success, or as the first sign that a once-great band had reached their creative acme three years earlier? Alternatively, can we say ‘neither’—is it possible to engage with Speaking in Tongues without fitting it into an overarching narrative about Talking Heads’ career?

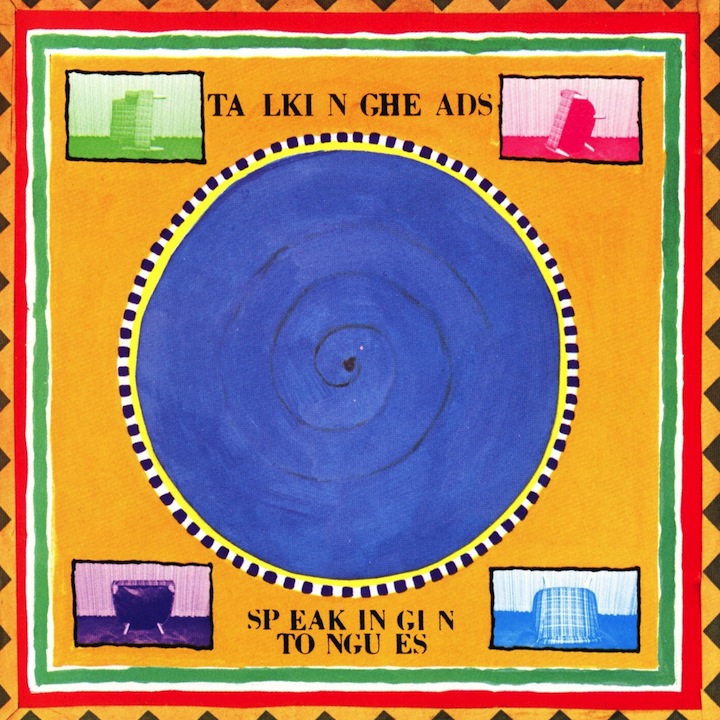

We might start with the title, a neat little package of polysemy. It is, as is well-known, a reference to the process that Byrne used to compose the lyrics to this album: in extensive jam sessions, Byrne would distill a wordless scat vocal melody in response to Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison and Tina Weymouth’s grooves, and fill in that melody with lyrics after the fact. (This was not a new process for Byrne—indeed, he had experimented with it during the sessions for 1979’s Fear of Music, the results of which can be heard in the outtake ‘Dancing for Money’.) More literally, however, it also refers to glossolalia: the spontaneous emergence, during moments of religious ecstasy and epiphany, of incomprehensible word-like sounds. This is an old practice, attested to in the New Testament itself, but one peculiarly associated with and inflected by 19th and 20th-Century American Christian groups: Mormons and Charismatic Pentecostalists. The charismatic style of engagement with the laity lead to the development of radio and television sermons, and it is no coincidence that several of these sermons became source materials for Byrne’s 1981 collaboration with Brian Eno, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. (The scientific-seeming term ‘glossolalia’ itself hides a kernel of gibberish: it is a transliteration of the Greek “γλωσσολαλιά”, literally “speaking in tongues”; thus the use of “glossolalia” to describe speaking in tongues is, technically speaking, profoundly redundant.) Perhaps most obviously, the title Speaking in Tongues gels with Talking Heads’ own band name in a way that none of their other albums does. The two placed side-by-side promise a veritable Babel of nonsense, a whole album’s worth of ‘I Zimbra’. This impression is only strengthened by the album cover’s wonky kerning (“TA LKI N GHE ADS SP EAK IN GI N TO NGU ES”), or the visual cacophony created by the overlapping translucent sheets of the limited edition’s Robert Rauschenberg–designed cover.

Instead of a performance of gibberish and the triumph of phonology over semiotics, though, Speaking in Tongues delivers a kind of clarity and immediacy that suggests that while glossolalia may well be the subject of the album’s content, it hadn’t influenced the album’s form. One of the album’s most famous moments is the injunction “Stop making sense!”, repeated several times towards the end of ‘Girlfriend is Better’—a phrase that would eventually give the band’s Jonathan Demme–directed 1984 concert movie its title. Yet, paradoxically, the Heads are here not leading by example, forming their request as a perfectly grammatical English sentence, as opposed to the Dadaist nonsense of ‘I Zimbra’. So too with the phrase “Check it out: still don’t make no sense” from ‘Making Flippy Floppy’, a song that captures the utter bewilderment that the facts of human existence can inspire. (The song’s bewilderment seems particularly related to sex—why else the focus on the strangeness of the human body, the invocation of the originary, Freudian relationship with the mother and the use of the phrase “rocket to my brain”?) ‘Moon Rocks’ even finds Byrne flippantly dismissing talk of flying saucers and levitation with a casual “Yo, I could do that”—hardly the pose of a committed irrationalist, but definitely the pose of a committed ironist. So while Byrne’s lyrics are quite frequently difficult to understand, they are never, strictly speaking, unintelligible.

The songs offer a musical clarity and immediacy in parallel with the lyrics. Most of them are strikingly simple, following the formula that the band pushed with Remain in Light: find a groove and stick to it, and elaborate on one theme. (Take ‘Making Flippy Floppy’ as an example—how different is the chorus from the verses? Where does the chorus even begin?) This, as Byrne notes in his book How Music Works, means that the band could not rely on things like sudden key changes or the juxtaposition of different melodies to sustain the listener’s interest; instead, the band would have to offer interesting grooves and textures, ones that could bear the weight of so many repetitions with little or no variation. Thus, as Byrne writes, “the tracks feel more trance-like, somewhat transcendent, ecstatic even—more akin to African music or Gospel or disco”. (Gospel, of course, comes through as a strong influence in ‘Slippery People’, with Nona Hendryx delivering call-and-response vocals, “Lord” and all, in the chorus.) There’s an airiness to the production, too, that feels refreshing after the beleaguerment frequently engendered by the full-spectrum, hyper-saturated sound of pop music circa 2013. Unadorned and direct, the songs of Speaking in Tongues have to be especially catchy in order to stay lodged in the listener’s memory.

Whenever I listen to Speaking in Tongues I find myself drawn back to the album’s final two songs, ‘Pull Up the Roots’ and ‘This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)’. The first is perhaps just a little too fast and jittery to seriously dance to; the galloping tempo and chittering keyboards threaten to throw any dancefloor into disarray, which seems perfectly apt for a song that features Byrne rhapsodising about the joys of going out of his mind. (Still, I often wonder why no bright young thing of the disco edit scene has yet put together a killer bootleg of the track; its nervy energy could surely be tamed by judiciously slowing it down and anchoring it with a solid 4/4 drum pattern?) The lyrics point towards an existence of delirious forward movement, constantly pulling up roots and severing connections: an appealing sentiment, as long as you, like the Heads, “don’t mind some slight disorder”. But the cost of that existence is a kind of perpetual mania, seeing a transcendental principle in the “coloured lights and shiny curtains” of motels, believing not only that “everyone else is like me”, but also that “every living creature” wants to pull up their roots, too.

‘This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)’, by contrast, expresses a bittersweet desire for stability and identity, but one profoundly tempered by a realisation that these things are only ever provisional, uncertain: “I guess that this must be the place”; “Share the same space for a minute or two”. This longing is one tinged with both ennui—“I guess I must be having fun”—and an undercurrent of dread. The song is haunted by death: Byrne asks his lover to “love me ’til my heart stops, love me ’til I’m dead”, and finally begs her to hit him on the head—a way of putting him out of his misery and sending him to his final home? If that reads as too dark an interpretation of this well-known and well-covered song, then that’s because of the plangent melody, which does much of the emotional heavy lifting here. The naïvety of the melody—bass and guitar playing the same theme, no counterpoint—has a wide-eyed innocence about it, and the simplicity of a nursery rhyme. Here are themes worthy of philosophy—life, death, love, belonging—wrapped into a bittersweet five-minute pop song that floats along in a pleasantly anodyne manner, as if in zero gravity. Finally the climax of the song, and the album: after forty-seven minutes of making sense despite themselves, the Heads close the album with Byrne’s wordless wail of pain, ecstasy and dread—not glossolalia, but a single vocalisation that finally, after all that effort, transcends words.