Tori Amos is hardly to blame for the existence of her fans’ expectations, nor for their disappointment when her work does not live up to them—but that doesn’t prevent that disappointment from feeling intensely personal, as though she’s slighting all of us when she releases an album as tepid as, say, 2009’s Abnormally Attracted to Sin. Of course, Tori is not the only recording artist who has ever disappointed their fans, but it is perhaps a testament to the emotional heft of her brilliant early work that we feel entitled to her very best work every time she releases a new album.

Every fellow Tori Amos fan—or, to use the cultish in-group terminology, ‘ear with feet’—I have met doesn’t merely like her work; they love it viscerally, passionately, and with the same mixture of overwhelming adoration and a kernel of hatred for that same adoration that characterises the most tempestuous of love affairs. Our love for Amos cathects around personal traumas, rough patches, periods of whole-of-life upheavals. (A friend of mine confessed that he once planned to commit suicide to the soundtrack of her song ‘Gold Dust’, because it was so perfectly sad, but that the opening couplets convinced him to go on.) We love her and her work, of course, but we also partially despise her for making us so craven.

These strong emotions make it difficult to be an ‘ear with feet’, or perhaps a former ‘ear with feet’, especially in the face of a decade-long decline in quality in her oeuvre after 2002’s Scarlet’s Walk (arguably her last truly strong album). We expect a ‘return to form’ with each new album, and instead she delivers something overstuffed—the three albums that followed Scarlet’s Walk average just under twenty songs each—and shockingly unedited, as if she couldn’t bear to part with a single song idea, no matter how banal. (How else to explain The Beekeeper’s ‘Ireland’, a banal piece of fluff whose opening line is “Driving in my Saab, on my way to Ireland”?) Perhaps the worst part is that there is always something redeemable in these albums, such as American Doll Posse’s twenty-third song, ‘Dragon’, a meditative and understated piece of uncommon beauty. This mixture of strong emotional investment and increasingly disappointing albums with a few redeemable features lends the relationship I and many others have with Amos’ work a hint of Stockholm Syndrome—no matter how bad she gets, we love her and hold out hope that next time, things will be better.

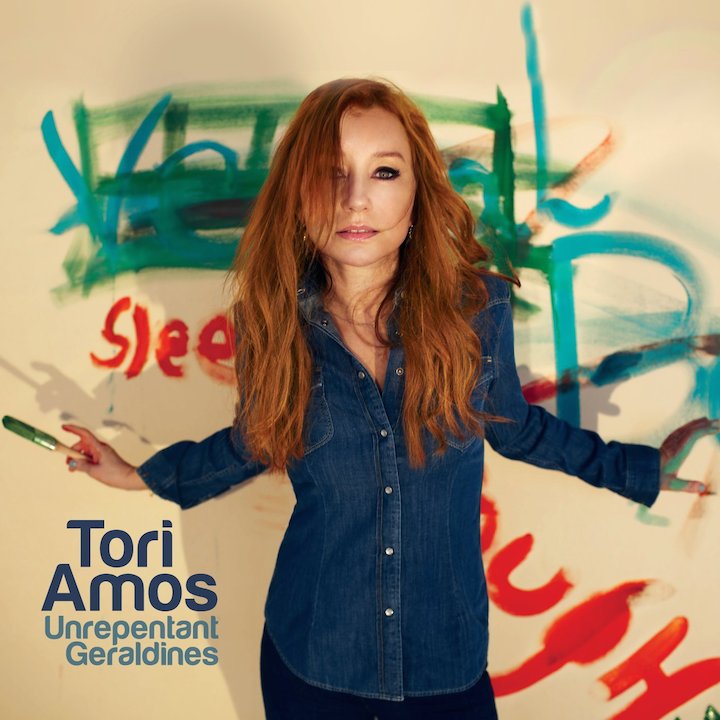

For my own part, I quit caring about Tori Amos’ new releases after 2009’s album of reinterpreted Christmas carols, Midwinter Graces (possibly the nadir of her career). Her projects since then have had a quiescent character about them: a classical album that pays tribute to Bach, Debussy and Schubert (2011’s Night of Hunters); a collection of orchestral reinterpretations of her back catalogue (2012’s Gold Dust). I was happy to avoid giving these more than a cursory listen—they seemed only to confirm that Amos was no longer in the business of attempting to make fresh, vital music, and had shifted from an artist with something to say to an artist interested primarily in tending to their legacy. And I would have happily ignored her latest, Unrepentant Geraldines, were it not for Alex Macpherson’s thoughtful and positive review of it in The Quietus.

Unrepentant Geraldines is by no means perfect—there’s the obligatory piece of undercooked whimsy (‘Giant’s Rolling Pin’), and at just under an hour, it’s still a touch too long—but in its directness it more than compensates for the oblique, costumed misfires of its predecessors. It’s relieving to hear that Amos is no longer aiming for (and missing) the grand theatricality of her earlier work, instead focusing on turning out well-crafted little gems of songs—ones whose lustre is dulled, perhaps, by age and wisdom, but which are no less beautiful for it.

For this reason Unrepentant Geraldines feels like a break from Amos’ usual pattern of massively overhyped new albums that promise a ‘return to form’ but deliver something else. By delivering something so contrary to our expectations, something that with its gentle reserve risks being perceived as underwhelming, Amos has begun a process of creative rebirth that could herald a second act in her career—and a new relationship to her work for her fans. Or, as she puts it on album highlight ‘Oysters’, “I’m working my way back to me again.”