Five Surprising Dancefloor Sensations

Bahumutsi Drama Group, ‘To the Comrades (PB edit)’

Over the past few years, the phenomenon of disco edits—fuelled by young dance music producers who want to cut their teeth by reworking previously existing songs—has been through a boom-and-bust cycle. What started off as a means of tweaking unknown songs from the archives for contemporary audiences has become something of a farce, with producers either not looking very far into those archives (see Soul Clap’s excellent edit of Jamie Foxx’s ‘Extravaganza’, the lustre of which is dimmed by the fact that ‘Extravaganza’ was barely five years old when Soul Clap applied the scalpel) or doing abominable things to well-known pop songs (if you must hear an example, then this edit of ‘Love Shack’ will suffice). This is something of a shame, though, because a good disco edit can act as a conduit between the past and present, startling us by making new connections and remapping our musical universes. For example, did you know that Cat Stevens made a weird cosmic disco track called ‘Was Dog a Doughnut’? Pilooski’s edit of the track does more than make it palatable for contemporary dancefloors; it also makes us rethink an artist whose work, by and large, has been unfortunately reduced to the shorthand ‘70s folkie; converted to Islam’.

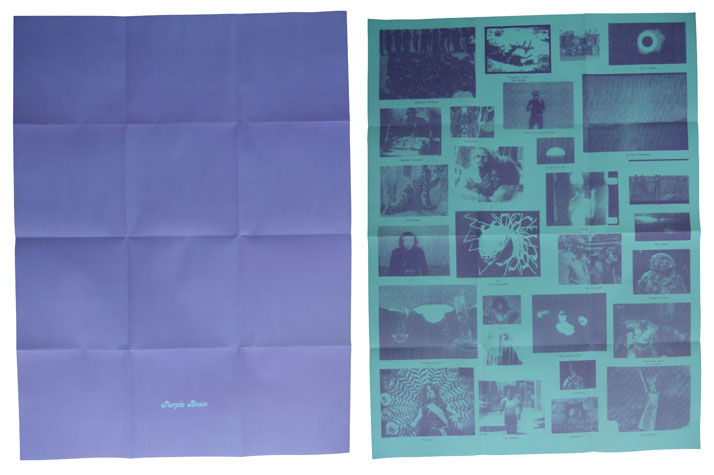

Production duo Purple Brain’s 2009 edit of Bahumutsi Drama Group’s ‘To the Comrades’ represents the logical end of the crate-digging arms race that the popularity of disco edits started. While producers like Pilooski and his peers dug deep, none of them would think to edit something as wilfully obscurantist as a song from anti-apartheid activist and playwright Maishe Maponya’s play Busang Meropa (Bring Back the Drums). This song was only ever released as a private pressing in South Africa; the ‘label’, Sounds from Bahumutsi, didn’t put out any further albums. Quite how two Australians living in New York ever discovered this rare slab of wax remains unclear.

In any case, we should be thankful that they did, because while their edit of ‘To the Comrades’ doesn’t perform the recontextualising work that makes the form so interesting, it does something rarer: it brings something genuinely novel out of the archive. ‘To the Comrades’ may have been composed around the same time Paul Simon’s album Graceland was introducing swathes of first-world listeners to the sounds of black South Africa, but its message and form couldn’t be more different. Instead of gently effervescent mbaqanga guitars, ‘To the Comrades’ is driven by a hard-edged synthesised bassline. Instead of offering generic, vaguely politicised nostrums (à la ‘Homeless’), ‘To the Comrades’ employs direct address to wannabe revolutionaries, asking them to reconsider the violence with which they pursue their aims: “My mother is in that house / My father is in that bus / I saw them go up in flames / Why do you punish them like that?”

The politicisation and directness are challenging, given that African music is often presented in the west as either cuddly, life-affirming spiritual music (see Graceland, or the soundtrack to The Lion King) or as the alien sounds of a completely incomprehensible Other (as in this ethnomusicological field recording of a Burundian ‘Chant avec cithare’, deemed sufficiently terrifying to be included in Swedish musician Fever Ray’s Halloween podcast for Resident Advisor.) In short, ‘To the Comrades’ presents a kind of African music not readily accessible to—or comprehensible by—the West.

Of course, bridging that cultural divide is made easier when the beats have been tweaked so the song can slide neatly into a DJ set at 128 BPM. If you like what you hear in the video above, the song can be found on Purple Brain’s CD and 7″ package for RVNG INTL.

Jan Turkenburg and His Pupils of the Geert Grote School, ‘In My Spaceship (Pilooski remix)’

How does a song recorded by a Dutch schoolteacher and his pupils over the course of a single day become a minor dancefloor sensation? Like nearly every recent musical success, ‘In My Spaceship’ only exists because of the power of the internet to disseminate diverse styles of music.

The story goes something like this: in 2004, Jan Turkenburg, a teacher at the Geert Grote School in Zwolle, the Netherlands, heard that submissions were open for a compilation titled Interplanetary Materials, to be released on the netlabel Comfort Stand. He started piecing together a song titled ‘In My Spaceship’ for the compilation—a song that would, to quote the compilation’s liner notes, express how he felt on ‘sleepless nights when I wish I just could beam myself up to my spaceship and leave everything behind.’ After one such sleepless night spent composing the song, Turkenburg left himself with no time to prepare for his music classes, and instead invited his students from four classes across the course of the day to help record the final track. The oldest students were tasked with writing their own lyrics (in English) and singing them; the middle grades with playing the glockenspiels and xylophones; and the youngest group with the charmingly raucous Dutch countdown that concludes the track.

The resulting song must have impressed the curators at Comfort Stand, because it made the grade for Interplanetary Materials. There’s a lot to be impressed with, too: the synth lead line—composed on a dinky Yamaha keyboard—hearkens back to the primitive electronic music of the early 70s, before Giorgio Moroder made arpeggiated synthesisers de rigeur in disco music. Turkenburg’s lyrics and melody have a certain pantomime charm about them, but it’s the pupils’ own naïve lyrics that really make the song: their main desires are to be rid of homework, having to tidy their rooms, and the pedagogy of one Mrs Hoogerman. (Poor Mrs Hoogerman.) There’s a sense, though, that Turkenburg doesn’t quite know what he’s created—that earworm of a lead line appears only halfway through the opening countdown, and the song is marred by an unfortunate use of novelty Star Trek samples. It’s also a little slow, and the sound quality is a bit dodgy. Were it not for the intervention of Dirty Sound System’s Pilooski, it’s doubtful that ‘In My Spaceship’ would have ever been heard outside of the small number of people who downloaded Interplanetary Materials.

Quite how Pilooski got his hands on ‘In My Spaceship’ remains murky. I recall reading around the time of his remix’s official release in 2010 that he had found it on a podcast and chased it to its source at Comfort Stand; but recent Google searches on the topic lead me only to dead links. In any case, I myself first heard it on a Dirty Sound System promo mix on their blog, Alainfinkielkrautrock, at some stage in 2009. I went about tracking it down, which took some time—this was back before Shazam made track identification so piddlingly easy; or, at least, before I had a phone that could run Shazam. I ended up with the original, which was then available for free on Comfort Stand’s website. The difference between the original and the remix was stark: without significantly altering the song’s melody or structure, Pilooski had given it some serious depth: kickdrums kicked harder, the synth line was more insistent, the vocals more evenly mixed. I had to wait several months, though, before I found out who was behind the remix and whether it would be available commercially, and it was only when it started appearing on other people’s podcasts that I finally figured out how to get my hands on this elusive track.

Since its commercial release, ‘In My Spaceship’ has gone through a decline as inexplicable as its sudden rise. It was given a lavish release—500 copies printed on picture-disc vinyl through Parisian label Sister Phunk, with accompanying t-shirts from French fashion house Kulte. Pilooski’s remixes and re-edits, while hardly mainstream, are also hardly obscure, and his productions invariably end up with high-profile DJ supporters. But for whatever reason, a mere three years later it’s hard to find out much about ‘In My Spaceship’. The label’s website has shut down, and the URL now directs to a generic holder website in Japanese; Googling the single’s artist and name leads to a bunch of dead links and/or illicit file sharing sites. Turkenburg’s own music is perhaps the most interesting casualty of the success of ‘In My Spaceship’—at some stage between its initial free release and its commercial reissue, he removed all of his work from the public domain and became a member of a performing rights organisation, which means his work is paradoxically harder to find now he’s had his brief moment of internet fame. I would direct you to his official website, but at the time of writing it has been infected with malware. The internet giveth, and the internet taketh away. ((Since the original publication of this article, Pilooski’s remix of ‘In My Spaceship’ has become available for purchase as part of Parisian fashion retailer Colette’s Colette Kids compilation.))

Fuck Buttons, ‘Bright Tomorrow’

Recently, and only for the briefest of periods, it seemed as though the next big thing in dance music was the kind that nobody in their right mind would dance to: noise music. In retrospect it sounds absurd, but it’s true: back in 2007 and 2008, the vanguard of electro-house got so abrasive and noisy that it might almost have been possible for a DJ to slip a Merzbow track into their set without anyone noticing.

This period didn’t last, of course. As electro-house painfully transitioned from underground genre du jour to one of the many ingredients thrown in the sonic blender known as ‘EDM’, most of its chief protagonists found themselves drawn to a nascent disco revival. But what might dance music sound like had the Ed Banger and Kitsuné sound that was so tremendously popular in 2007 kept pushing towards the abrasive and ugly? Well, it might sound something like Fuck Buttons’ ‘Colours Move’.

In many ways, Daft Punk’s album Human After All charted electro-house’s course in the years after its 2005 release. Human After All was a harsh bummer of an album compared to the heady, joyous blend of classic FM rock and soft disco Daft Punk popularised with their 2001 album Discovery. But even if it was a critical and commercial failure, it was prescient, and its chief flaw seems to have been that its form matched its content too well. The dystopian subject matter and spiky, discordant production were matched with wearyingly repetitive song structures.

Seen at the time as Daft Punk’s epigones, production duos Justice, Digitalism, and Simian Mobile Disco married those harsh guitar textures and aggressive drums to catchy hooks and clever pop song structures. This trio released their three debut albums within weeks of each other in the middle of 2007, and soon enough their buzzy, noisy approach to dance music was beating a path from the underground to the mainstream.

Even though these groups’ best-known songs—such as ‘Phantom’, ‘Zdarlight’, ‘It’s the Beat’—had an unfriendly patina of harsh saw-wave synthesis, crunchy bass kicks, and tinny treble hisses, they also honed in on their audience’s pleasure centres with direct drum patterns and insistent melodies. Daft Punk—who saw which way the wind was blowing long before this subgenre-defining trio of albums was released—cannily mounted a 2006/2007 world tour which combined elements of their entire oeuvre to create a sound not dissimilar to that of the groups they had inspired.

If Daft Punk had taken this subgenre full circle, it was one of the supporting acts on that tour that would push this hissy, noisy dance music almost to its breaking point. Sebastian Akchoté, who records and DJs under the name SebastiAn, scored his first breakout dance floor hit with ‘Ross Ross Ross’, a blast of chopped-up samples and chunky house drums. He soon began to make his records even more difficult on the ear: ‘Walkman (re-edit)’ ends with a cathartic cascade of screeching feedback, while ‘Motor’ samples (or replicates) the sound of an F1 race-car engine to produce a track whose only mooring to the world of club music is its kick-snare house beat.

Around this time, too, noise musicians started making overtures towards dance music. Growing, a Brooklyn-based duo whose career arc began in making slow, portentous drone/doom music not unlike that of early Earth, started adding rhythmic components to their sheets of airy guitar dissonance. At the time, it seemed as though a rapprochement between the two genres of music was almost inevitable. At that very moment, Fuck Buttons entered the scene.

‘Bright Tomorrow’ is the closest thing to a dance track on Fuck Buttons’ 2008 debut, Street Horrrsing. The rest of the album cleaves closely to a blend of power electronics and ambient drone (‘Sweet Love for Planet Earth’), sometimes with clattering rhythm tracks (‘Ribs Out’). The fact that it comes from a noise band entering dance territory rather than vice versa shows in a number of ways but none of this detracts from the song’s primary virtue, which is an understanding that both noise music and dance music are designed to offer moments of transcendence. Dance music achieves this through rhythm, while noise music achieves it by enveloping its audience in raw sound. ‘Bright Tomorrow’ does it with both, which lends the track an air of the ecstatic so powerful it’s hard to resist grinning like an idiot even as it splits your eardrums.

As we now know, this brief moment of rapprochement didn’t go on to transform dance music. There was only so far producers could push it, and SebastiAn crossed that line in early 2010 with ‘Threnody’—a thirteen minute track, then purportedly from his forthcoming album Total, that included eleven minutes of a slowly rising drone tone. The backlash from SebastiAn’s fans was swift and fierce, and when Total appeared after several delays in 2011, ‘Threnody’ was a notable absence. Fuck Buttons, for their own part, recruited veteran dance producer Andrew Weatherall for their sophomore effort, Tarot Sport—an excellent album, but one whose slick professionalism lacks some of the knockabout charm of Street Horrrsing.

The conjunction between noise music and dance music is a strong nexus, however, and one that has been explored since the early days of Throbbing Gristle. You can hear it in Carter Tutti Void, The Knife, and Dead Fader, amongst others. Dance music’s current form may seem inevitable in retrospect, but there’s nothing stopping us from looking back in order to find a better way forward.

Norma Jean Wright, ‘I Like Love’

When Daft Punk’s ‘Get Lucky’ became a number one single in Australia on May 12 of this year, it did more than merely signal the long-awaited return of the world’s favourite robot-helmeted duo. Aside from being a shot in the arm for the flagging career of Pharrell Williams (whose recent solo work has been—let’s be honest—received with deserved indifference), it also marked the return of Nile Rodgers’s signature guitar style to the charts. It was no accident that Daft Punk chose ‘Get Lucky’ as the lead single from their latest album Random Access Memories—aside from the fact that it’s an excellent piece of bubblegum disco-pop, it also makes the album’s back-to-the-future production style and aesthetic plain by slathering Rodgers’s guitar work everywhere.

Even if you don’t know who Nile Rodgers is, if you have turned on a radio at some stage over the past forty years you will have heard his guitar work, all of it played on one single 1953 Fender Stratocaster (retrofitted with a 1960 neck). Aside from his first band, Chic—responsible for a raft of disco hits including ‘Everybody Dance’, ‘Good Times’ and ‘Le Freak’—he has co-written, produced, or otherwise appeared on a number of tracks that are not so much ‘well-known’ as part of the twentieth century’s musical fabric: Madonna’s ‘Like a Virgin’, David Bowie’s ‘Let’s Dance’, INXS’s ‘Original Sin’, Diana Ross’s ‘Upside Down’, Sister Sledge’s ‘We Are Family’, The B52s’ ‘Roam’. This is before we consider the number of times he has been sampled, and the songs that have stemmed from those samples (including Sugarhill Gang’s ‘Rapper’s Delight’, the first ever commercially successful rap single, and Modjo’s ‘Lady (Hear Me Tonight)’). When he appeared as a headliner for 2012’s Golden Plains festival, several of my friends said, ‘Who?’, and had to be cajoled to attend his performance. By the end of his set—which incorporated nearly all of the songs listed above—we were all grinning like idiots, astounded by the extent to which Rodgers had shaped the sound of popular music since the late seventies.

We were hardly the only ones to notice. Rodgers’s life and career have recently been the subject of a critical re-evaluation prompted by the release of his memoir, Le Freak: An Upside Down Story of Family, Disco, and Destiny, and the comprehensive four-disc Chic box set Savoir Faire (which promises to be the first of many). What is curious about this critical re-evaluation, though, is the manner in which it shapes our access to the music that Rodgers has worked on. In essence, it picks winners and losers from a vast discography, rendering some tracks more accessible than others. Nowhere is this more acute than Norma Jean Wright’s ‘I Like Love’, a track that Rodgers and his production partner Bernard Edwards wrote, produced and helped perform for her eponymous debut album, Norma Jean. Quite why this little gem of a track has been sidelined from overviews of Rodgers’s career remains baffling to me, given that many less worthy tracks—including the relatively flaccid Debbie Harry number ‘Backfired’—continue to be considered integral parts of the Rodgers/Chic canon.

The pleasures of ‘I Like Love’ are simple, but instructive. The track opens with that signature Rodgers guitar sound —clean, plangent, precise, and laden with its own inherent percussion. Bernard Edwards’s warm, rich bass shortly joins. Then the sucker punch: Norma Jean’s breathy vocal rushes in, bringing with it drums, syrupy strings, and horns—all of the ingredients required for classic disco. Lyrically speaking, it isn’t terribly profound—don’t most of us also like love?—nor is it musically very complex, but this simplicity only underscores the quality of Rodgers and Edwards’s arrangement and playing. There are no tricks in the song’s progression—just chorus, verses, then an extended breakdown and buildup to the song’s climactic, and ecstatic, restatement of its theme. It’s utterly simple, but, despite this, very few contemporary dance music producers are writing songs of this calibre, preferring instead to oversaturate their tracks with screaming synthesisers and stadium-shaking sub-bass.

Despite the fact that Norma Jean was released by one of the highest-profile independent record labels of its day (Bearsville) and distributed by a major label (Warner Brothers), it remains relatively neglected today. The vinyl edition is long out of print, and the most recent reissue (in 2011) was by Edsel records, a relatively obscure British reissues label without a major-label distributor. You can, of course, buy it on iTunes (and I encourage you to do so), but it’s highly unlikely that many copies have been shifted that way—in the face of so much choice, consumers tend to focus on a small number of winners, and many millions of tracks listed on iTunes have not yet sold a single copy. Thus despite its major-label history and hitmaker pedigree, ‘I Like Love’ remains relatively unknown and definitely under-appreciated—a hidden banger if ever there was one.

Talking Heads, ‘(Nothing But) Flowers’

As the title of this series suggests, the songs it has dealt with have been ‘hidden’ in some way: neglected by history, birthed in obscurity, cloaked in abrasive noise, or simply unjustly underappreciated. These are, perhaps, some of the most obvious ways music can be hidden, and indeed some of these aspects of music are sufficiently desirable that they can be used as marketing devices. (I would never have heard Purple Brain’s edit of ‘To the Comrades’ had I not purchased their limited-edition 7″/CD bundle—and I wouldn’t have purchased it if it hadn’t possessed the ineffable cool factor of being a limited edition and featuring deeply obscure music.) However, there are many more ways for something to hide, including that most paradoxical form of hiding: hiding in plain sight.

Talking Heads’ ‘(Nothing But) Flowers’ doesn’t try to hide in plain sight: it was released as the final single for what would turn out to be their final album, Naked, and indeed it was their second most successful single ever on the Billboard Mainstream Rock charts, despite being neither very mainstream nor very rock. (Their most successful track on the same chart is, bizarrely, ‘Wild Wild Life’, which perhaps proves that when it comes to Talking Heads’ songs, chart performance shouldn’t be the starting point for a discussion of aesthetic merit.) Nonetheless, it has since slipped into a kind of genteel disrepair in the Talking Heads canon, having been later pipped to the post as the last proper Talking Heads single by ‘Lifetime Piling Up’ from the compilation Sand in the Vaseline and by being part of an album that, in retrospect, sounds like a band recording its own eulogy. (Michael Hastings of AllMusic, for example, argues that “the album’s elegiac, airtight tone betrays the sound of four musicians growing tired of the limits they’ve imposed on one another.”) Then there’s also the matter of critical reappraisal in the internet age, where writers have easier access to the entire Talking Heads catalogue and can breezily proclaim, almost as if in unison, that Remain in Light is the artistic acme of the band’s career.

Another way to put it: if you’ve not heard many Talking Heads songs, it’s unlikely that ‘(Nothing But) Flowers’ will be among that number. Posterity has been very kind to a number of the band’s songs, many of which weren’t terribly successful upon their release—such as ‘Psycho Killer’ (which peaked at number 92 on the general Billboard chart), ‘This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)’ (number 62), and ‘Once in a Lifetime’ (number 103)—yet this song remains something of a hidden gem in the band’s discography, for reasons I can’t quite fathom. Everything excellent about Talking Heads is here in one place. There’s the band’s penchant for collaboration and genre experimentation—The Smiths’ Johnny Marr plays guitar on this track, alongside African session musicians Abdou M’Boup, Yves N’Djock, and Brice Wassy (known as the “king of 6/8 rhythm” and admired by none other than Fela Kuti). There’s an amazing beat and bassline, provided by one of rock music’s most unobtrusive and dependable rhythm section, Tina Weymouth (bass) and Chris Frantz (drums). There’s an excellent vocal melody of the kind that David Byrne specialises in, written after the groove had been recorded and inhabiting it perfectly. Finally, it continues the band’s extensive exploration of textual irony by being a song about a post-human future narrated from the point of view of a nostalgic remnant of the twentieth century whose weltanshauung was formed at (what was then considered) the height of mankind’s destructive excess.

This textual irony means that the song is ferociously difficult to pin down to a single meaning. Critics have long been divided about what, exactly, the song is trying to say: for Robert Christgau, it’s “a gibe at ecology fetishism”; for Pitchfork’s Joe Tangari, it’s “a wistful celebration of the end of civilization”. Is it pro- or anti-capitalist, anti- or pro-environment? Byrne himself, in his book How Music Works, offers only an oblique comment in the form of an anecdote about how the lyrics were written: while driving around suburban Minneapolis, he was struck with the image of a future America in which the economy had collapsed and the strip malls and housing developments had decayed into a feral state. “The twist was,” Byrne writes, “that this scenario allowed me to also frame the song as a nostalgic look at vanishing sprawl, a phenomena I hadn’t thought that I was terribly sentimental about. It was obviously ironic in intent, but it also allowed me to express a love and affection for aspects of my culture that I had previously professed to loathe.”

This richly layered irony might explain the strange effect of ‘(Nothing But) Flowers’ when played, at loud volume, as the final song of a DJ set. You would expect the groove to be tinged with sorrow as the dancers are reminded of the ecological catastrophes that humankind has wrought; instead, though, the song has a celebratory edge, a musical ebullience that the lyrics can’t quite tame. While Byrne’s narrator laments the disappearance of “cherry pies, candy bars and chocolate-chip cookies”, the band behind him suggest a colourful riot of animal and plant life reclaiming North America’s barren suburban sprawl. Thus the effect is one that encourages celebration in spite of the song’s elegiac tone; we know that we are poised on the brink of destruction and a future that will not be kind to those humans that remain, but we dance on anyway.